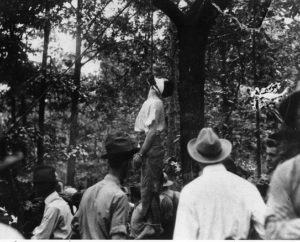

The Lynching of Leo Frank

The name Leo Frank (1884-1915) rose to fame for highly violent reasons. Accused in 1913 of murdering a thirteen-year-old girl who worked at the Atlanta National Pencil Factory (where Frank was a manager), a sensational and heavily flawed trial ensued.

The body of Mary Phagan was found in the basement of the factory; most modern historians hold that Frank was innocent and the man who provided testimony against him was actually guilty. In Georgia, Frank was sentenced to death. The case was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, where a conviction against Frank was upheld 7-2. The governor of Georgia at the time, John M. Slaton, however, convinced of the inaccuracy of testimony presented, commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison.

According to Jonathan Weisman, in his 2018 book (((Semitism))), “Frank’s lawyers maintained that Jim Conley, the black janitor at the factory, was the killer, and in the decades after the trial, researchers who secured Frank’s ultimate pardon have said that was likely so. To convict a Yankee Jews, the prosecutors had the delicate task of relying on a black man’s testimony in front of an all-white Southern jury. They portrayed Conley a a simple man, too stupid to have made up the complicated story that hung the murder around Frank’s neck, a story that involved Frank dictating a practically illiterate ‘murder note’ to Conley to frame the night-watch man who had discovered the body.”

In 1915, Frank was kidnapped from jail and lynched by White Supremacist members of the group Knights of Mary Phagan, led by a former governor and president of the Georgia senate. Telling their wives they were going out fishing, they drove to Milledgeville, GA, where Frank was imprisoned, broke in, kidnapped Frank and hung him. While his lynched body hung, they composed a song, the “Ballad of Little Mary Phagan.” They then retired to Stone Mountain where they proceeded to burn a cross and announce the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. None of these kidnappers and murderers were ever convicted, though their names were well-known.

Following the violence, half of Georgia’s 3,000-large Jewish community fled the state, the Temple in Atlanta opted to change much of its customs for the sake of assimilation (what Jonathan Wesiman calls the “low-profile bunker mentality”), and the Anti-Defamation League was founded.

In 2002, the American Jewish Archives received a heretofore unknown cache of letters written by Frank while in jail following his conviction. The letters are between Frank and well-known investigative journalist and former Montana lawyer C.P. Connolly (1863–1935) who reported extensively on the Frank trial for Collier’s Weekly and petitioned openly for Frank’s innocence.