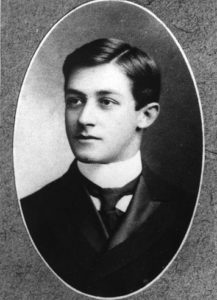

Binationalism, Rabbi Judah Magnes, and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Rabbi Judah Leon Magnes (1877-1948) is memorialized as a leader of Reform Judaism, a notable pacifist during WWI, and an advocate for a binationalist Jewish-Arab state during the years of the British Mandate of Palestine. Born in San Francisco, California, Magnes became one of the most widely recognized voices of American Reform Judaism in the 20th century, eventually emigrating to Mandatory Palestine and serving as the first chancellor and later president of the Hebrew University (1925) in Jerusalem.

While Magnes chose to immigrate to the Mandate of Palestine in 1922, he maintained the general belief of Reform Judaism at the time in opposition to a nationalist Zionist movement; he believed Diaspora Jewry of equal importance to Jews who made Aliyah (moved to Eretz Yisrael) and furthered that a vibrant Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine would only serve to enhance diasporic Jewish life. This was important because many Jewish who settled in Mandatory Palestine (and many Jews in Israel to this day) opted for the view that returning to Eretz Yisrael was of greater value than any Jewish life one could lead in the Diaspora.

Maintaining that immigration to Mandatory Palestine was a matter of personal choice, Magnes rebuked the notion that Aliyah “negated” the Diaspora or supported the Zionist cause. In Magnes’ belief, a state in Eretz Yisrael should be built in either a “decent matter,” or not at all. He valued his post at the Hebrew University because he saw the school as an ideal place to encourage and indulge Arab and Jewish cooperation. Such cooperation became Magnes’ life-long passion. In 1929, as revolts led to bloodshed across Palestine, Magnes called for a binational solution and rejected the UN partition place. He continued to fight for this solution for the rest of his life.

The binational, or “one-state solution,” advocates for a single state in Israel-Palestine in which inhabitants of all ethnicities and religions are granted equal rights, citizenship and autonomy under the law. Magnes dedicated his life to pursuing this solution. He rejected a solely Jewish state and worked for reconciliation with Palestinians; in response, Magnes was heckled and attacked by fellow Jews both local and abroad, as well as in the international Jewish press.

Magnes died in 1948, z”l, five months after the founding of the modern State of Israel, never seeing his work towards a binationalist state reach fruition.